Land, Legacy and Trust

Land, Legacy and Trust

WRITTEN BY JON MACNEILL, COMMUNICATIONS MANAGER

Darran O’Leary knows the countryside and homesteads of western Charlotte County so well he can hardly finish a story about one property without interrupting himself, mid-sentence, to tell you a piece of local lore or funny anecdote about another.

We’re driving through Scotch Ridge, Darran telling us about the ‘bunny ears’-shaped property that is next to a patch of land included in the Skutik IPCA (Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area), when it happens again.

“That’s Brian’s place,” he says abruptly, pointing to a bungalow enveloped by the IPCA. “He’s doing the big game study for us. He can leave his front door, hop on the bike, and run the trails to scout the best places to put up cameras, do the field work.”

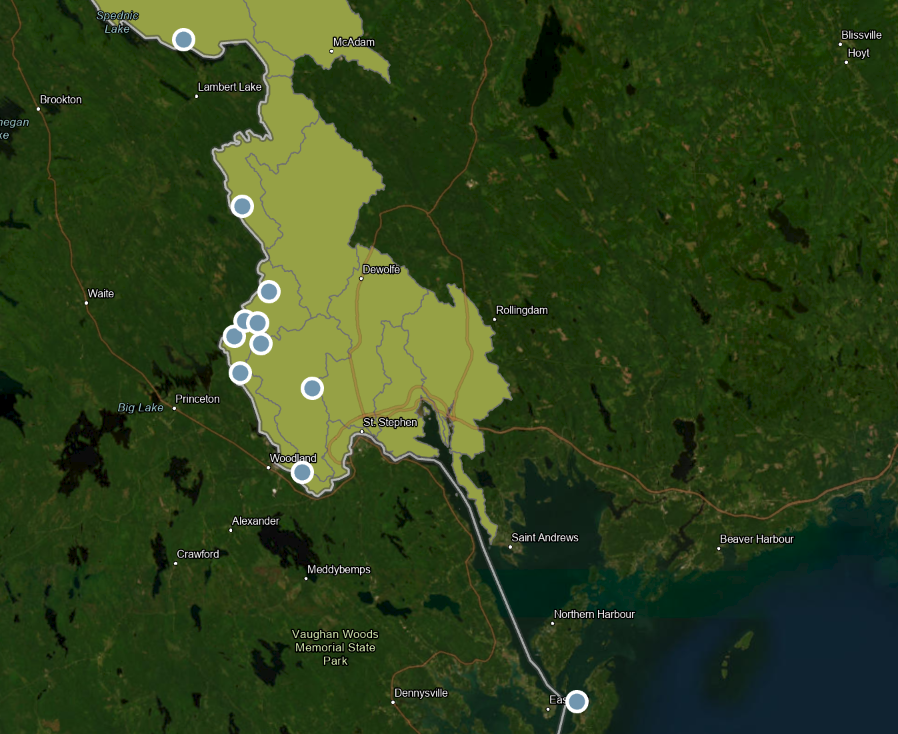

Eleven properties (blue dots) form the Skutik IPCA, stretching from Hardwood Island in Spednic Lake to Campobello Island, the map's southernmost point. The highlighted area marks the Skutik watershed, with the white line showing the Maine-New Brunswick border.

“He says he has the best job in the world.”

Darran smiles. You get the sense that, most days, he might challenge that title for himself.

The Peskotomuhkati land manager is one of the core architects behind the Skutik IPCA, a 1,500-hectare protected area like no other in New Brunswick, standing as a unique model of conservation and cultural renewal.

These protected properties rest within the watershed of the Skutik (anglicized as Schoodic, or the settler-named St. Croix River) and Passamaquoddy Bay (the anglicized version of their Nation’s name), land that sustained the Peskotomuhkati way of life since time immemorial: hunting caribou, tapping maple, digging clams, taking seal and porpoise, fishing and gathering. The recently-restored Salmon Falls is where they once fished Atlantic salmon, the natural obstacle of the falls slowing the mighty fish enough to make them easier to spear. Pesokotomuhkati translates into English as ‘the people who spear pollock.’

“We’ve got roughly 25 kilometres of riverfront that in some form or fashion is almost continuous and is now protected by the Nation,” Darran says.

“It’s pretty awesome to say this is what we’re doing—protecting not only the land in general but also the land for future community members to enjoy and use and for them, in turn, to protect.”

The land conservation project takes on even greater significance when you consider that the Peskotomuhkati are not recognized as a First Nation in Canada. For decades, they’ve been fighting for recognition from the federal government. As such, they have no official territory, no reserves to ensure their culture carries on.

So, for the past six years, they’ve been establishing their own through this protected areas partnership with the Nature Trust of New Brunswick.

As far as either side is aware, it’s a unique relationship in Canada. The Peskotomuhkati, led by Darran and staff under the direction of Chief and Council, work to identify the lands, and the Nature Trust acquires and holds the Title of Deed under a Lands Holding Agreement until the Nation develops its own land trust infrastructure, at which point the lands will be officially transferred to the Peskotomuhkati’s ownership and care.

“Nature protection is the perfect vessel for bringing Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities together”

“To be honest, we went into this thinking we could help them develop a land trust and do conservation because our organization has a long history of doing this work successfully,” says Nature Trust CEO Stephanie Merrill. “But the reality is, the Peskotomuhkati have a much longer history of taking good care of the land, and the lessons we’ve been able to learn from them are invaluable. It has evolved into so much more.”

Stephanie remembers her first time meeting Darran, shortly after becoming the Nature Trust’s CEO three years ago. At that point, the IPCA partnership was well underway, but with the change in leadership, its future wasn’t guaranteed as far as the Peskotomuhkati were concerned. If Darran didn’t feel like he could build a connection with Stephanie based on sincerity and trust, the project would end right there.

“People always want to know how we formed this partnership, and I guess we take it for granted now,” Darran says. “It takes a bit of work, but you have to sit down and have a conversation first, build some trust.”

“You have to be vulnerable, you have to let your professional guard down, so to speak, to create the space where you can build common ground,” Stephanie adds.

“But once that level of trust is there,” Darran says, “if you have a common end goal, the differences in how you get there can be overcome.”

The view of the Skutik River behind Chiputneticook Lodge on the MacNichol-Orser Conservation Easement, the 926-hectare property that was the beginning of the Skutik IPCA.

For the Nature Trust, working with the Peskotomuhkati has meant learning to view conservation through an Indigenous lens. Traditional Western conservation practices often start and end with protecting land for its pure ecological value. But for the Peskotomuhkati, land stewardship is inseparable from culture, history, and community. The land tells a story, and every ecosystem is treated as an interconnected whole, meant to sustain both people and nature.

“For Western organizations, conservation has often meant ‘fence it and forget it,’ assuming any human presence spoiled the land’s value,” Stephanie says. “The Indigenous worldview is much more inclusive of humans as a part of nature, and that using land to support ourselves in a balanced way, is actually a much healthier, more sustainable perspective to have—and that it can be quite compatible with conservation outcomes.”

On Peskotomuhkati lands, a plant doesn’t have to be rare or endangered to be considered worthy of protection; common plants hold cultural value, cherished for traditional practices. Historical features like shell middens or abandoned homesteads—human impacts that many non-Indigenous conservationists would consider a blemish—to the Peskotomuhkati are part of the land’s history and are celebrated as a piece of the legacy they’re trying to protect.

The IPCA partnership between the Nature Trust and Peskotomuhkati has also strengthened both groups' connections with the Wolastoqiyik and Mi'kmaq Nations in New Brunswick.

“Because we’re not recognized as a Nation, it’s been difficult at times to have a working relationship. But through this project, we’ve come to play a key role with the other Nations, and we’ve seen how much stronger we all are together,” Darran says.

“That’s one of the most powerful things, I think: that we do work so closely with them (the other Nations) now, and it’s through the common goal that we’ve been able to build those relationships.”

Looking to the future, both Darran and Stephanie agree that even long after the Peskotomuhkati have been officially transferred the Title to the IPCA lands, the story won’t end there—they’ve built something special here.

“We’ve established ourselves as innovative, leading organizations in this challenging work of reconciliation through conservation, so I think the opportunities will be whatever we dream them to be,” Stephanie says, noting she and Darran have been invited to several conferences and gatherings to speak about the unique partnership. “There is so much work still to be done with respect to the biodiversity and climate crises, we've got to find ways to row together to make even more positive outcomes.”

Nature protection is the perfect vessel for bringing Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities together, Darran adds.

“I tell everyone, any new piece of land that we get is not only for us as a Nation, but for everyone who wants to see it protected and enjoyed by great grandkids and great, great grandkids—and not just Indigenous children and those generations, but non-Indigenous generations,” he says.

“Because everybody’s got a soft spot for nature—for a baby porcupine or a baby raccoon. Something is going to tug at your heartstrings. Maybe it's a walk through the woods, maybe it's a trip down the river in a canoe, maybe it’s an animal—something tugs at your heartstrings on a daily basis, makes your blood pump, so coming together to protect nature, it's just too easy to get behind.”

“It doesn’t matter what we do today—if we walk through a park, through the woods, to the river—something catches somebody’s eye and somebody says, ‘today’s a good day.’”

This story is featured in our 2023-24 Gratitude Report, our annual report. You can read the digital version here. Members and donors receive a hard copy in the mail each December—donate here to join the mailing list. Want to learn more about our work on shared stewardship with New Brunswick’s Indigenous communities? Click here to read a feature story about our initiative to rename some of our preserves with Indigenous names in collaboration with Wolastoqey elders.